The women behind the Manhattan Project that Nolan’s new film ‘Oppenheimer’ completely ignored

- Nolan’s «Oppenheimer» fails to highlight the women who helped make the Manhattan Project possible.

- Women worked across the Project, including as explosion techs, librarians, and hematologists.

- Several went on to shape their fields later in their careers, with one even winning a Nobel Prize.

Yet, the film fails to depict a key part of the story, using scientists Lilli Hornig and Charlotte Serber as stand-ins for all the women who contributed their time and expertise to make the project possible.

From a Nobel Prize winner to a chemist who protested the use of the atomic bomb in warfare, the work of these women was essential to the story Nolan sought to tell — and yet, their voices remain mostly absent from the film.

Here are the stories of just six of the hundreds of women that made essential contributions to the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos.

Lilli Hornig

Chemist Lilli Hornig first came to the United States in 1933 from Berlin, Germany after German officials threatened to imprison her father in a concentration camp. Hornig first arrived at Los Alamos after Manhattan Project officials tapped her husband to join the effort.

Hornig began researching plutonium — a key element for nuclear technology. However, after her colleagues realized how dangerous the isotope plutonium-240 was, they fired her, citing concerns that the isotope would cause reproductive damage. Hornig told the Voices of the Manhattan Project she recalled trying to point out that men’s reproductive systems were more exposed than hers.

Hornig then moved to the explosives team and witnessed the Trinity Test — the world’s first detonation of a nuclear weapon, conducted in New Mexico in 1945 — before leaving Los Alamos. Hornig, notably, also tried to stop the actual use of the atomic bomb in warfare, signing a petition urging officials instead to demonstrate the bomb’s power on an uninhabited island.

«And we thought in our innocence — of course, it made no difference — that if we petitioned hard enough they might do a demonstration test… and invite the Japanese to witness it,» Hornig said in the interview. «But of course the military, I think, had made the decision well before that they were going to use it no matter what.»

Charlotte Serber

Charlotte Serber first went to Los Alamos with her husband, a physicist, in 1942. Serber worked for the Manhattan Project as a scientific librarian — despite not having any formal training — handling various top-secret technical documents throughout her time at Los Alamos, according to the book, «Their Day in the Sun: Women of the Manhattan Project.»

Serber eventually became the only female group leader at Los Alamos, overseeing a staff of 12 people.

She also assisted with counterespionage efforts, making trips into nearby Santa Fe to act drunk in local bars and spread rumors that the project was actually an effort to build an electric rocket, according to the book, «Atomic Spaces: Living on the Manhattan Project.»

Floy Agnes (Naranjo Stroud) Lee

Floy Agnes (Naranjo Stroud) Lee was earning her biology degree from the University of New Mexico when she was asked to work at Los Alamos. Lee worked as a hematologist, collecting blood samples from the men who worked directly on the atomic bomb. Her work was essential in monitoring scientists’ health at Los Alamos.

In an interview for the Voices of the Manhattan Project — an oral history archive — Lee recalled taking blood from physicist Louis Slotin after he was exposed to severe radiation doses during a 1946 experiment. Lee said she was worried he would die — which he did, just nine days later.

A member of the Santa Clara Pueblo tribe, Lee was one of a few Indigenous women working at Los Alamos. After the war, Lee earned her Ph.D. in zoology from the University of Chicago and went on to pioneer a new method for computer analysis of chromosomes. Lee was also a founding member of the American Indian Science and Engineering Society, an organization that still exists today with the mission of increasing representation for Indigenous peoples in STEM fields.

Joan Hinton

Joan Hinton was a physics graduate student at the University of Wisconsin when she was tapped for Los Alamos. She worked on a team building the first reactor able to use enriched uranium as fuel. Hinton also witnessed the Trinity Test.

Just weeks after the US dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagaski, killing more than 200,000 people, Hinton drove physicist Harry Daghlian to the hospital after he was exposed to a lethal amount of radiation from a plutonium core. He died about three weeks later.

Hinton believed the bomb would be used in a demonstration for the Japanese — which Hornig advocated for as well — and became an ardent peace activist after the war. In protest, Hinton sent the mayor of every major city in the United States a case filled with glassified desert sand — a byproduct of the Trinity Test bomb — alongside a note asking whether they wanted their communities to suffer from a similar fate, according to her obituary in the New York Times.

Hinton emigrated to China in 1948, where she spent the rest of her life working on dairy farms.

Elizabeth Graves

Elizabeth Graves was an invaluable member of the Los Alamos team because she was one of few physicists in the United States with experience using a Cockroft-Walton particle accelerator, a machine that could produce beams of charged particles and was essential to the development of the Manhattan Project, according to the US Department of Energy.

Graves was also pregnant during her initial months at Los Alamos and even went into labor while conducting an experiment. She did not stop until the experiment was finished, timing her contractions with a stopwatch, physicist Henry Barschall told the authors of «Their Day in the Sun.»

Graves and her husband went on to raise their family at Los Alamos, where she continued to research experimental nuclear physics.

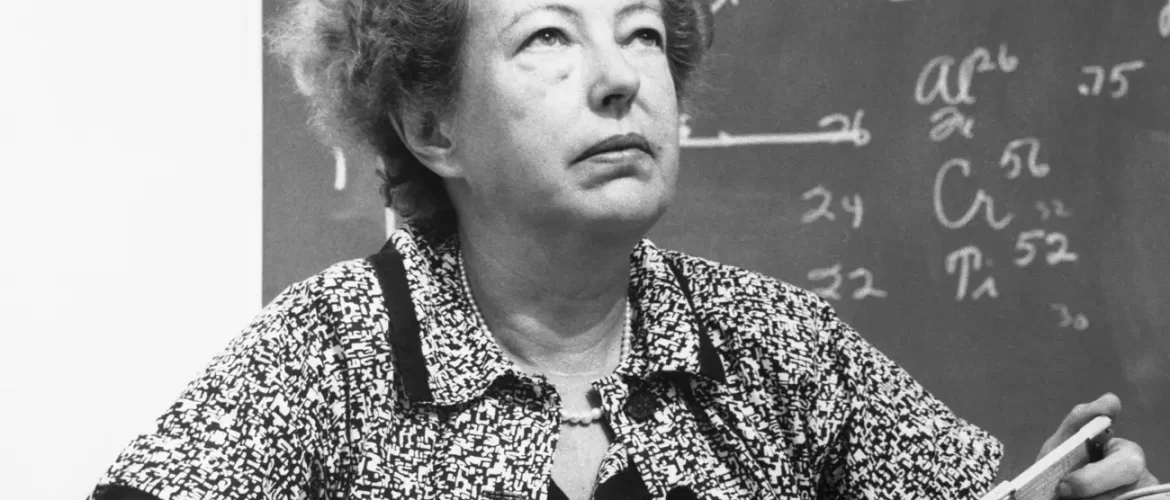

Maria Goeppert Mayer

Theoretical physicist Maria Goeppert Mayer contributed to the development of nuclear fission while working at Columbia University, Sarah Lawrence College, and visiting Los Alamos from time to time. Mayer never worked on the atomic bomb under Oppenheimer, rather working with Edward Teller on the related hydrogen bomb at Los Alamos.

«Keeping from him that awful secret of the atom bomb research I did during World War II for four years was harder on me than all the prejudice of the years,» Mayer told Sharon McGrayne for her book, «Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles, and Momentous Discoveries.»

«We were lucky because we didn’t contribute to the development of the bomb, and so we escaped the searing guilt felt to this day by those responsible,» Mayer added.

In 1963, Mayer won the Nobel Prize in physics. She was only the second woman — preceded by Marie Curie in 1903 — at the time to receive the award.